Dyes

..".Oils are also occasionally added to mordants, esepcially in Turkey-red (with Morinda citrifolia) dyeing. The Balinese use coconut oil, the people of Nusa Tenggara candlenut oil (Aleurites moluccana), while the Batak of Sumatra favour buffalo lard."

Warp ikat

"Warp ikat fabrics are often woven on a continuous warp in the remoter parts of the archipelago where older forms of the traditional technology have survived. Peoples such as the Batak of Sumatra and the Toraja of Sulawesi use warp ikat, as do many of the inhabitants of the interior of Borneo such as the Iban."

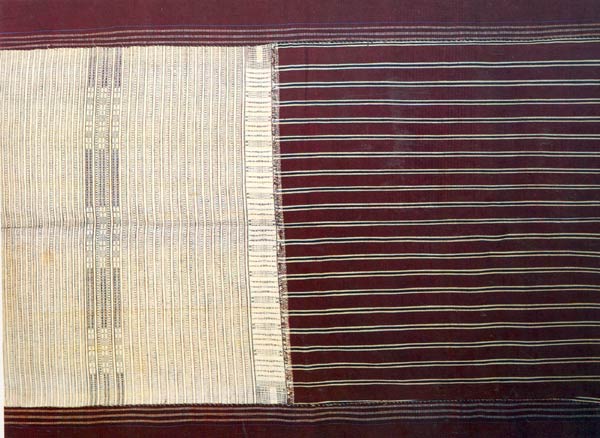

Karo Batak cotton textile, kain

uis, decorated with warp ikat and metallic supplementary wefts. Collected

by Prof. M. A. Jaspan in Sumatra. 168 x 77 cm.

Hull University, CSEAS 73.74•

Warp ikat

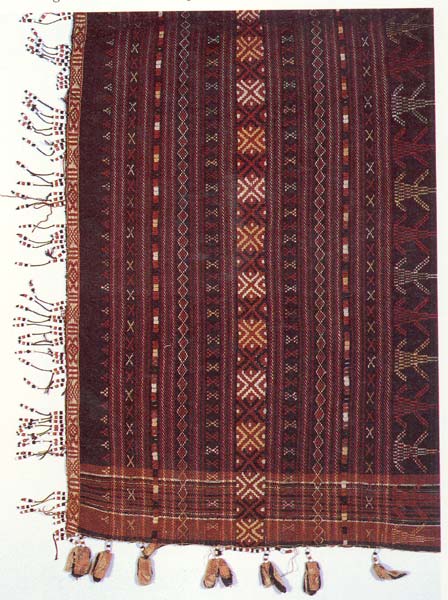

Toba Batak-style textile, Ulos padang rusak, woven in heavy cotton and decorated with warp itak, twining and fringes. Collected in Bali, 1982. 188 X 74 cm.

"The art of dyeing with traditional materials and methods can be unpredictable, and dyers sometimes observe special rituals in order to ensure the success of the undertaking. On Roti spirits are said to dip their hands and breasts in the dyebath, depriving the dye of its effectiveness, and talismans made of strips of Iontar palm and three kinds of hen feathers are suspended above the liquid. Christian Rotinese use a plaited cross or mark a cross on the ground with lime powder before dipping the yarn in the dye. Pregnant and menstruat¬ing women are not allowed near the dyebath. The Toba Batak observe a similar custom and forbid pregnant women from participating in dyeing. Toba Batak dyers also have to refrain from talking about death, and nobody is allowed to come near the dyebath unless they are working. On Sumba dyers work in walled or fenced enclosures, away from prying eyes, and in Borneo the Iban traditionally venerate female deities who are credited with teaching humans the art of dyeing. "

Tapestry

"The Batak of north Sumatra use bands of slit tapestry in some of their brocaded textiles, and among the Iban this kind of weaving is incorporated into the broders of men's jackets."

Supplementary weft

Ragidup textile, made of separate panels sewn together, decorated with stripes, supplementary weft, supplementary warp and fringes. Woven in a mixture oi heavy cotton and svnthetic varns. Toba Batak, S,amosir Island, Sumatra. Collected bv Prof. M. A. Jaspan 248 x 111 cm. Hull Universitv, CSEAS 69.58.

Batak shoulder-cloth, ulos,

from north Sumatra. Decorated with metallic supplementary wefts, warp ikat,

twining and fringes. Collected by Dayid Eunice. 170 x 68 cm. Hull University,

CSEAS 1986.1-3.

Batak textile, ragidup, woven with a cotton supplementarv warp and a metallic supplementarv weft. Made from separate panels sewn together, the fabric also has twined borders and fringes. A modern verrsion of one of the most sacred Batak textiles whose name can be translated as 'pattern of life'. Collected bv David Eunice in Sumatra. 216 x 33.5 cm. Hull Universitv, CSEAS 1986.1-2.

"The Batak, another Sumatran group, use supplementary weft to make detailed designs on fabrics known as ragidup."

"Twining and drawn threadwork

Twining is another widely distributed textile technique and is known in Timor, Sumba and Sumatra (among the Batak). In this process a set of weft yarns, which are often multihued, are twisted around one another in the same plain. This method is commonly used to bind loose warp ends after weaving to prevent fraying."

Beadwork

Beadwork is often used to decorate textiles. Imported multi-coloured glass beads have long been popular... The Ankola Batak are antoher Sumatran group who incorporate beads in their fabrics."

"As well as being a feature of many folk models, the sexual division of labour is a common theme in Indonesian mythology. As has been recorded by Sandra Niessen (1985), for example, the Toba Batak possess a legend known as the myth of Tunggal Panaluan, in which male-female opposition is perceived in terms of weaving (women's work) and writing/magic (men's work). In this myth male and female twins are born already equipped with the tools of their respective professions - the boy with sacred texts and the girl with weaving implements. Later in life when their parents try to set them tasks that girls and boys do together the twins steadfastly refuse: the boy wishes to devote himself solely to the magical arts, while the girl wants only to weave. The link between women and the preparation of textiles is referred to in other Batak legends, like the tale of the girl who was turned into an ape for refusing to spin yarn. Yet in another Batak legend, which describes how a young woman was exiled to the moon because she was more interested in spinning than marrying, the converse occurs: this myth emphasises moderation when dealing with potent female symbols such as textiles."

"In addition men make a major contribution to the production of cloth within a traditional context. Since they are responsible for wood-working, they produce much of the equipment used by the women, such as gins, spindles, spinning-wheels, swifts and looms. A craftswoman, therefore, may be dependent upon her father, husband or even son for part of her livelihood. Among some Indonesian peoples the process of weaving is seen as an expression of the interdependence of men and women, sometimes with sexual connotations. Thus the Batak liken the bamboo shuttle to the penis, as do the Makasarese and Buginese who traditionally believed that if a man held this weaving implement he would be rendered impotent. There is also a Javanese myth which tells of a weaver who drops her shuttle and promises to marry whoever retrieves it. When the shuttle is brought back by a dog, she is honour-bound to marry the animal. While the shuttle may be associated with the male, both the cloth and the yarn from which it is made are usually considered as female. Among the Toraja, for example, the words for weaving and vulva are etymologically linked, and textiles are traditionally likened to the female sexual organs."

"Birth is the occasion on which sacred textiles are brought out in many Indonesian societies. ... and Batak grandparents customarily provide cloths that are credited talismanic properties."

"In addition to coming-of-age festivals textiles feature prominently in the customs associated with courtship and marriage. Until the early twentieth century such was the importance of weaving among peoples like the Sundanese and Sasak that young women were expected to prepare certain cloths before they could get married. According to Batak tradition, the potential success of a union could be gauged from the amount of cloth that had been woven. Should a suitor enter a village and find that the girl he had come to visit was weaving a textile which she had only just begun, then a marriage would be unsuitable; if, however, the fabric was nearly finished, then the converse would be true. "

"It is the cutom for Batak couples to receive the gift of a textile from the bride's father; a prestige cloth may also be wrapped around the groom's mother by the bride's family to symbolise the union of the lineages."

"Because Indonesian peoples subscribe to a variety of different belief systems and religions the body may be treated in different ways after death. ... The non-Muslim Batak, for example, lay the body in state on red and blue ikat cloths..."

"The mourners themselves may adopt a specific form of dress in order to attend a funeral. On the morning of a funeral the Balinese wear white head-cloths, whil the Batak tie indigo-dyed ikat fabrics around their heads."

Shoulder-blanket used in ritual gift exchanges in north Sumatra. Handwoven cotton decorated with supplementary wefts, tapestry, twining and beaded fringes. Angkola (Mandailing) Batak, early 20th century. British Museum, 1970. AS6.6.